.

Today, my latest story, "The Star-Bear," goes online at Tor.com. It was edited by Jonathan Strahan and illustrated by Bill Mayer. The illustration is directly above.

To mark the occasion, I've written an essay explaining what went into this particular story, why I wrote it, and some of its hidden allusions. I recommend that you go to Tor.com and read the story first and then come back and read what I had to say. Then again, there are people in this world who eat dessert first. You know which type you are better than I do.

You can find the story here. Or you can go to Tor.com and poke around. It's well worth doing.

Writing "The Star-Bear"

I used to be president of the world.

Okay, technically I was president of the International Union

of Writers1 and it was only an honorary position. But the honor

meant a lot to me because it had been arranged by my friends in Russia. I’ve

been to Russia several times over the past two decades and attended Roscon, the

national SF convention, twice and Aelita, the country’s oldest SF convention

three times (one of them virtual). I had the opportunity to become good friends

with many writers, and fans there. I think the world of them.

There is something about Russia, or perhaps I mean the

Russian people, that grabs you by the heart. It’s elusive and hard to explain,

but I’ve heard it called “the strangeness of the Russian soul.” Puzzling over

that strangeness led me to write two stories set in Siberia, “Libertarian

Russia” and “Pushkin the American.”2 As the titles will tell you,

they were genre, not mainstream.

Then the Russian army invaded Ukraine. I had no choice but

to resign my position with the IUW.

My Russian friends were outraged. They had bought into

Putin’s potent mix of truths, half-truths, slanders, conspiracy theories, and

lies. I happened to know something of the subject, so I posted an essay online explaining

why the claim that the U.S. had 32 “bioweapon labs” in Ukraine, ready to

unleash plagues upon their helpless motherland was a dark fantasy and ridiculous

to boot. If anybody there read it, nobody was convinced. Someday the war in

Ukraine will end. But I doubt I’ll ever be welcomed back by the Russian science

fiction community that had so warmly embraced me.

It is a sad thing to lose a friend. Sadder still to lose

many friends all at once, along with a country I’d come to care about. Not a

fraction as sad as what every citizen of Ukraine is now going through, of

course. But sad enough that I wanted to write a story about that loss.

* * *

The hero of that story was based on an émigré writer named

Alexei Remizov—a modernist, satirist, calligrapher, and student of folklore.

When he fled Russia in 1921, he was held to be an important writer. In Paris,

he gained the admiration of such luminaries as James Joyce and Vladimir

Nabokov, but the passing decades saw his prominence dwindle. He alienated the émigré community and

outraged Nabokov by applying for and receiving a Soviet passport. But though he

was obviously tempted, he did not return to his native country. Which was

probably a good thing, for many writers who fled and then returned did not live

long after. When he found himself unpublishable, he created unique stories

combining illustrations and a calligraphic text, which could be enjoyed only by

a single reader at a time. He died in 1957, well on his way to being forgotten.

I anagrammatized Remizov’s name to Zerimov because what

little I knew of Remizov’s life didn’t fit with the story I wanted to tell. His

wife Serafima, for one, did not die in Moscow but went into exile with him.

While Remizov was teaching Russian in Paris, he became friends

with the classicist Jane Ellen Harrison and her companion Hope Mirrlees, author

of the fantasy novel Lud-in-the-Mist. His work had a strong influence on

Mirrlees, so she and Jane made the most fleeting possible appearance in the

story—you’d miss it if I didn’t point it out—as “English bluestockings” Zerimov

teaches at the Ecole des Langues Orientales. There is also a reference to Jean

Cocteau’s Le Cap de Bonne-Espérance, and the claim that a genius

could build upon its innovations to create something astounding. Which Mirrlees

did in Paris, a Poem, printed and published in chapbook form by none

other than Virginia Woolf. The late scholar Julia Briggs called the poem “modernism’s

lost masterpiece,” and those few of us who have made a study of it are all convinced

it must surely have been an influence on T. S. Eliot, who was a close friend of

Mirrlees.

So there is a great deal hidden in this story which no sane

person would expect you to be able to winkle out. Here’s an example: When

Zerimov describes his first encounter with the Star-Bear, making claws of his

fingers and saying, “It reared up and went: Raowrr!” This line I took

from my late friend, Andrew Matveev. As a young writer, it was his ambition to

be the Russian Hunter S. Thompson. The editor he submitted his first novel to

jabbed the typescript with his forefinger and said, “This novel will never be

published.” Then he had Matveev sent into internal exile. In Ekaterinburg, he

was given a job as night watchman at the zoo, to keep him out of the way. In

the small hours, the big cats there made it clear what they wanted to do with

him. After Perestoika, Andrew (never Andrei) Matveev was free to write and

publish. But, he said, “A part of what I could have been was taken away from

me.”

I could go on and on. But I am not trying to impress you

with my cleverness. I simply hold up these sources so you can appreciate how

much more than you can see goes into even the simplest and most straightforward

of stories. That bit of fluff you enjoy so much? That too. All of a writer’s

life goes into every story, and a great deal of effort goes into hiding that

fact. Because, as William Butler Yeats wrote in one of his poems, “A line will

take us hours maybe;/Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,/ Our stitching

and unstitching has been naught.”

I hope you read my story, which the good folk at Tor have

made available online for free. But if it doesn’t work for you on the surface

level, as a simple tale of a man and a bear and possibly a woman, all this

background will be for naught. Still, if you do read it, I hope it gives you

pleasure.

The story’s title was borrowed from Remizov’s bear-story “The

Star-Bear,” one of four by him that appeared in The Book of the Bear,

translated and edited by Harrison and Mirrlees.

1 The IUW was founded in Paris in 1954, hit hard

times with Perestroika, and now its membership is almost entirely Russian,

though there have been efforts in recent years to make it truly international

again. If you know the history of the last seventy years, this should tell you

a lot.

2In one, a young post-Collapse Russian, enamored

of American cowboy movies, travels across Siberia and discovers why “Russian”

and “Libertarian” are incompatible terms. The other is about a 19th

century American stranded in Ekaterinburg, who becomes his new nation’s most revered

writer. Which I admit was pretty cheeky of me.

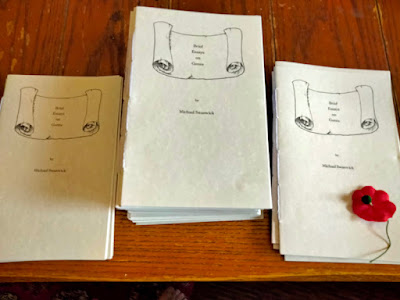

Above: The Illustration for "The Star-Bear" was, as I said, made by Bill Mayer. I think he did a terrific job of it.

*