.

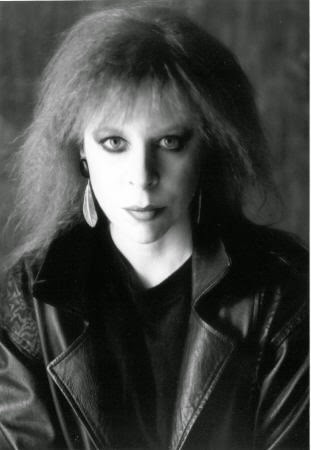

I have just now heard from a reliable source that

Tanith Lee has died. This is terrible news for lovers of fantasy. Her prose was elegant, sensuous, a delight to read. There really was no other writer like her.

I never met Ms Lee, so I have no stories about her to share. So instead, I'll give you the section of my essay,

"In the Tradition..." dealing with her work:

If there is one commonality among the hard fantasists, it is

that they are not a prolific lot. Tanith

Lee, however, is prolific. Which makes

it hard to single out one work for examination.

A survey of her oeuvre would

necessitate the exclusion of other writers.

Nor can she simply be skipped over.

She is a Power, and has earned her place here.

I've chosen to focus on Lee's Arkham House collection Dreams of Dark and Light not only in the

name of ruthless simplification but also because it is a rare thing for a hard

fantasist to work much in short fiction (novels being the preferred length of

eccentricity, and eccentricity being the name of the game) and rarer still for

one individual to excel at both lengths.

Here's a quick sampler of what happens in Dreams of Dark and Light: A selkie beds a seal-hunter in trade for the

pelt of her murdered son. The dying

servant of an aged vampire procures for her a new lover. A writer becomes obsessed with a masked woman

who may or may not be a gorgon. A young

woman rejects comfort, luxury, and the fulfillment of her childhood dreams, for

a demon lover. These are specifically

adult fictions.

There is more to these stories than the sexual impulse. But I mention its presence because its

treatment is never titillating, smirking, or borderline pornographic, as is so

much fiction that purports to be erotic.

Rather, it is elegant, languorous, and feverish by turns, and always

tinged with danger. Which is to say that

it is remarkably like the writing itself.

In "Elle Est Trois (La Morte)" three artists--a

poet, a painter, a composer--are visited by avatars of Lady Death. The suicidal allure of la vie boheme, with its confusion of death, sex, poverty and the

muse, has rarely been so well conveyed as here.

The artists are captured as their essences, each courting death in his

own way. The composer France unwittingly

acknowledges this when he tells his friend Etiens Saint-Beuve, "One day

such sketches will be worth sheafs of francs, boxes full of American

dollars. When you are safely dead,

Etiens, in a pauper's grave."

After France himself has been taken, the poet Armand Valier

muses on Death's avatars (the Butcher, the Thief, the Seducer) in Lee's

sorcerous prose:

. . . And then the third means to destruction, the

seductive death who visited poets in her irresistible

caressing silence, with the petals of blue flowers or

the blue wings of insects pasted on the lids of her

eyes, and: See, your flesh also, taken to mine, can

never decay. And this

will be true, for the flesh of

Armand, becoming paper written over by words, will endure

as long as men can read.

And so he left the

window. He prepared, carefully,

the opium that would melt away within him the iron barrier

that no longer yielded to thought or solitude or wine. And

when the drug began to live within its glass, for an instant

he thought he saw a drowned girl floating there, her hair

swirling in the smoke. . . . Far away, in another

universe, the clock of Notre Dame aux Lumineres struck

twice.

This is the apotheosis of romantic decadence--sex, drugs,

and death mixed into a single potent cocktail. But, lest the reader suspect her of indulging

in mere literary nostalgia, Lee notes in passing that "the poet would have

presented this history quite differently," by introducing a unifying

device, such as a cursed ring. This sly

contrasting of the story's sinuous structure with the clanking apparati of its

Gothic ancestors, does more than just establish that the fiction is an

improvement on antique forms. It hints

(no more) that the real horror, the real beauty, the real significance of the

story, is that death is universal. She

is a true democrat, an unselective lover who sooner or later comes for all,

aware of her or not, the reader no less than the author.

Once upon a time the Romantics elevated the emotions above

reason, sought the sublime in the supernatural and the medieval, and elevated

the equation of sex and death to cult status.

Following generations took their machinery and put it to lesser ends,

much as the forms of magic were taken over by performers of

sleight-of-hand. They could do no better,

for they had lost the original vision.

Lee's work is a return to sources and a rejuvenation of that

original vision. It is the higher

passions that matter. Viktor, the bored

aristocrat in "Dark as Ink" is too wise to pursue his obsessions, and

for this sin suffers a meaningless life and early death. But the eponymous heroine of "La Reine

Blanche" finds redemption despite her singular regicide and unwitting

betrayal of her fated love because she has stayed true to her passions. An erotic spirituality shimmers like foxfire

from the living surfaces of this book.

By some readings (though not mine) these works could be

classified as horror. There has long

been a midnight trade between the genres, ridge-runners and embargo-breakers

smuggling influences both ways across the borders. It's illegal, we are all agreed, but is it

wrong? No one would dare attempt to

expel the late Fritz Leiber from the Empire of the Fantastic. Yet he readily admitted that nearly all his

work was, at heart, horror. Even his

Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories, though disguised by ambiguously upbeat endings

and the wit and charisma of their heroes, exist in an almost Lovecraftian

horror-fiction universe. In the end, the

only question that matters is whether the work suits our purposes or not.

"As I supposed," says a raven in one of these

tales, "your story is sad, sinister, and interesting." Exactly so.

There are twenty-three stories in this volume, and I recommend them all.

Copyright 1994 by Michael Swanwick. Probably the best way to memorialize Tanith Lee would be by reading one of her books.

*