.

I am in the process of amassing a small but very fine collection of Pegana Press books. The most recent is

The Age of Malygris (Poseidonis Cycle I), a slim collection of one prose poem, two stories, and a poem by

Clark Ashton Smith. Plus two large illustrations by Smith himself and an introduction by

Donald Sydney-Fryer, of which more soon.

This first thing that has to be said about this book is that it's beautifully made. My "nano-press" publisher wife, Marianne Porter, opened it and practically swooned over the paper. And it has that deep, tactile print that you get from letterpress. And then there's all that business with typography and layout and such that people who care about fine printing get quite emotional about. Which I have to admit

does look quite nice.

But for me, it's all about the prose. So here's the first paragraph of

"The Muse of Atlantis," Smith's first piece in the book:

. . . Will you not join me in Atlantis, where we will go down through streets of blue and yellow marble to the wharves of orichalch, and choose us a galley with a golden Eros for figure-head, and sails of Tyrian sendal? With mariners that knew Odysseus and beautiful amber-breasted slaves from the mountain-vales of Lemuria, we will lift anchor for the unknown fortunate isles of the outer sea; and sailing in the wake of an opal sunset, will lose that ancient land in the glaucous twilight, and see from our couch of ivory and satin the rising of unknown stars and perished planets.

There is only one place where Atlantis, Tyre, Odysseus, and Lemuria can coexist and that's in the great continent of Romance, which is encircled by the Ocean of Story. Nor were there ever many who could describe that continent so well as did Clark Ashton Smith.

That kind of lapidary prose, by the way, is even harder to write than it looks. I know because, like everyone who encounters CAS at the right age, I tried to emulate it. Only, of course, to fail. It turns out that the first step in learning to write prose like that is to become a poet.

This brings me to the introduction, written by poet

Donald Sidney-Fryer, who has the happy distinction of not only being influenced by Clark Ashton Smith but of having met him as well.

The intro is chiefly an examination of CAS's poetic virtues, but it also touches lightly upon the man's difficult life. As a ruling whimsy, Sidney-Fryer postulates that the fantasist we know was merely a single reincarnation of (as H. P. Lovecraft dubbed him), Klarkash-Ton, High Priest of Atlantis. Which seems fitting for a man whose fantasies may well have served as an escape from an often hardscrabble existence.

Donald Sidney-Fryer also insists that

"The Last Incantation" and

"The Death of Malygris" are not stories but prose-poems, and as a poet himself he would know. But as a prose fantasist, I must insist that they are stories as well, and ones I enjoyed greatly.

Finally, I should mention that at $125, this is a costly little item when compared to your average mass market paperback. However, for a hand-made and lovingly-crafted book, issued in a limited edition of only fifty-five copies, it's a steal.

This is a volume that Clark Ashton Smith would have loved.

You can find information about the book

here. Or you can just to go the Pegana Press site and wander around by clicking

here.

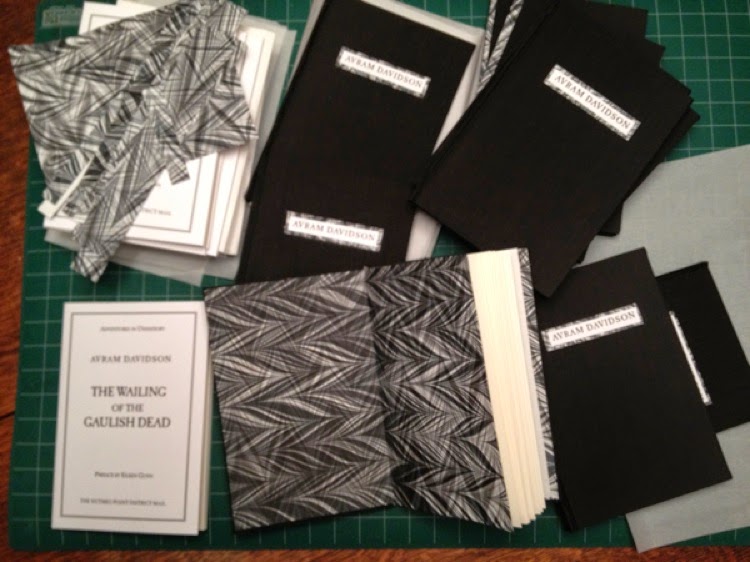

Above: In this photo the label looks a little worn; but actually it's printed on a quite lovely paper with a pattern of gold streaks criss-crossing it. Marianne admires it greatly.

*