.

Depicting Mexico and Modernism: Gordo by Gus Arriola/Mexico Y El Modernismo: Gordo de Gus Arriola

The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum

December 13, 2023 - May 5, 2024

Dr. Nhora Lucía Serrano is an Early Modern Comparative Literature scholar at Hamilton College. Recently, she curated a show at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum in Columbus, Ohio, on cartoonist Gus Arriola and his syndicated comic strip, Gordo. Michael Swanwick and Marianne Porter joined her via Zoom for a conversation about the exhibit.

Michael Swanwick: This is, I believe, the first retrospective of Gus Arriola's work ever. It seems almost impossible, given how popular that comic strip was when he was drawing it.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: During Gus's lifetime, toward the end of the run of the strip and after he retired, there were shows in Carmel and Monterrey in Southern California, where he resided and because he was friends with Eldon Dedini and other local cartoonists. In 1968 Gus did one show with Dedini and Charles Schultz at the Richmond Art Center in California. In 1983 he did another show with Dedini and Hank Ketcham (American cartoonist who created Dennis the Menace). Lifelong friends, Dedini and Arriola exhibited many times together in their lifetime. However, these exhibits all took place in Southern California and, as we know, at the time the bigger draws were Dedini, Ketcham and Schultz, who were very well known, and drew in lots of people. But Schultz, Ketcham and Dedini were very much friends with Gus Arriola, and they respected him and his artistry and his storytelling.

But until this exhibit at OSU there hasn't been a non-Southern California show that really has an international draw, and by that I mean the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum exhibits are meant to be national shows. So “Depicting Mexico and Modernism” is the first retrospective by this categorization of “international/national,” implying that the audience is meant to consist of folks beyond a particular local region.

The other reason why I would say it's a retrospective is that even those shows with Schultz, Ketcham, and Dedini were meant to be sort of snippets of his cartoon work, certain strips in conjunction. The Carmel Art Association also did an exhibit, but it was just more highlights of his artwork, not to the large scale that is “Depicting Mexico and Modernism.”

There were lovely shows back in the sixties, the seventies and the eighties. Even in the nineties, I think there was one show. But this is the first retrospective in the sense of you see the original strip at the beginning and you see the development of the strip throughout its 40- year run. It's really giving you the body of work of Gus Arriola, from the strips on the wall to the items in the cases, so as to give first-time visitors to Gus Arriola’s Gordo a sort of holistic understanding. And to fans like yourself, to enjoy a lot of different samplings as best as possible.

Michael Swanwick: Your show has what looks to be the first strip for Gordo. It is an amazing thing to see, especially if you're familiar with what he quickly became. He started out as a lazy, unkempt slob and he very soon became the exact opposite of that. He was very nattily turned out, quite a ladies man, and in his way he was hard working.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Yes, it's incredible. On the gallery wall, I decided we would have the first strip so people could see the original first strip. But we blew it up as a large decal, so that people could read it bigger. It's obviously bigger than the original newspaper size. The Billy Ireland does own the original strip. Visitors are welcome to go see it as well as a lot of the strips. But yes, you see, right away in that first strip that it was Gordo and his nephew Pepito: the language and the dialect, what he was doing, all of which was in that moment of the 1940s. Very quickly he changed things, but he changed them slightly, and he kept changing and, I would say, evolving. But that first step is important for everyone to see, whether you read Gordo or not, just to see where it started.

Michael Swanwick: At that time so much of American humor was ethnic. Fat, angry Germans, drunken Irishmen! There was a stereotype for everybody.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: I would agree. There was a stereotype for everybody, and we have to remember that this is Southern California and that Gus Ariolla's first job out of high school was with Screen Gems, being an animator, hanging out in Hollywood and being influenced by Hollywood's caricatures and representations of ethnic characters. Many newspapers at the time referred to Gordo as the Mexican Li’l Abner. Even Gus did. It was his first strip, his first moment.

Marianne Porter: The elevator pitch.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Exactly, and that also explains, if we are all familiar with Al Capp’s Li’l Abner, the way it was written with that sort of phonetic sounds of the language, a mock dialect to convey the main character. Of course it too slowly evolved to something else. But I would agree with you, Michael, that was the standard. We have to remember the context of the time in which this was created.

Michael Swanwick: At some point, Arriola started going to Mexico. All the accounts of the strip make a big deal about how he became an “accidental ambassador,” as was said, for Mexican culture. But I think at the same time that Mexican culture enriched his strip tremendously when he brought it in.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: I agree. He was of Mexican heritage. He grew up knowing some Spanish, and being exposed to the culture. I'm a firm believer that, as he said in many interviews, his intent was to explore and to showcase his Mexican heritage.

In the strip at the beginning, as well as, as you said, the elevator pitch—a Mexican Li’l Abner—he started to explore and to learn more about Mexico. Essentially, his drawings were based on—and again, we have to remember the forties and fifties—postcards, tourist magazines, right? There was no Internet or YouTube. So he was using references, other illustrations is the way I think of it. And in 1960 he decided, with his group of cartoonist friends, including Dedini, whose photos are in the exhibit, to go to Mexico. It was something of a homecoming for him and it changed the direction of the strip in an impactful way. If you study the whole strip, he felt more liberated and began playing with the story visually as well as story-wise. There was limited space in the gallery, not enough to show an episode carried over a month or two. But also he was really into telling stories that didn’t need to be episodic.

After that trip, the strip sees Mexico not just as ‘Over There Across the Border,’ but as Gordo’s world. There's a certain celebration in it that became much more vibrant, and I don't mean that just color-wise, just more relaxed, more playful. Which is lovely, and it was always there. It's playful, but there's certain freedom with it after the sixties, and that's where I think a lot of his playing with modernist art started to come in. He saw Mexican pottery in Mexico. He saw the Aztec culture in the buildings, and it's just something... I wouldn't say Mexico popped up, but just to you could see it sort of permeating more.

Marianne Porter: So Gordo's profession changes from farmer to tour guide. When did that happen? Was that when Gus went to Mexico, or was it before?

Nhora Lucía Serrano: That's a great question. It was before Mexico. So that's why it wasn't like when Gus went physically to Mexico everything changed in the strip. He had already been on this pathway, really. So if we talk about the early strip and the ethnic caricature, he had already changed Gordo from its early caricature representation before his trip to Mexico. Gordo was indeed a bean farmer at the who was also seen as being lazy. The transformation is to ne is no longer idle, he is now driving a bus (Haley's Comet), and he's showing everybody, including readers, all the different places in Mexico. More of the Aztec culture. He’s flirting with the American women who come down to Mexico, but also saying, “Hey, let’s go over here.” Or the tourists say, “Let’s go see this.”

To me, that's very reminiscent of the fifties and sixties Hollywood movies where they were essentially travel movies. I'm thinking of the Bing Crosby and Bob Hope road movies. I'm thinking of one of my favorite old movies, Charleton Heston's Secret of the Incas. In that movie, if you look it up online Heston is wearing the Indiana Jones jacket and fedora and the whole outfit. And that's what Steven Spielberg based the whole costume on.

Marianne Porter: Heston did some very strange movies in his time.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: I would agree. And there were a lot of movies at that time that were essentially exploring foreign lands. You know, precursors to a lot of movies today. So to your question. Gordo was a bus driver before Arriola went to Mexico, but Gus Arriola had already started to change the strip and go, “Wait a minute. I want to do something different.” So he started to do something different in the strip, and he became very curious to see the places in Mexico.

Michael Swanwick: I want to mention that all the exhibit captions are in Spanish and English both, which I thought was very graceful for this particular strip.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Oh, thank you. Thank you so much. It was something I decided early on. There were two reasons why. As a curator, you look at the gallery space and what it has to offer you. I had to make choices based on the space, but I also wanted to tell a certain story, and I knew I wanted the walls to be just the strip and the display cases to show other items related to the Gordo strip. I wanted the strips to be the highlight of the show. So that's why it's "Gordo by Gus Arriola."

But I also knew that I wanted to do a bilingual show for two reasons. One, the strip introduced Spanish words at the time, and always used Spanish throughout the duration of the strip. I thought doing a bilingual signage for the displays, section titles, wall labels, and everything else would be organic to the intent of what Gus Arriola wanted for Gordo. So that was something I thought it would highlight. I wanted to have Spanish and English in the show, not just in the strip, to normalize bilingualism.

And the other reason was, I wanted to do a show, an exhibit, where families from the Latino community could come and read one of their own. Besides the fact that I love Gus Arriola and Gordo, I wanted to do the retrospective show for so many reasons. One of them was, I wanted the Latino community to see one of their own.

One of my lifetime projects is that the history of American comics should include in its canon ethnic cartoons and Gus Arriola. A question that I always return to: Why isn’t Gus Arriola more known in the mainstream? So I wanted the Latino community to see that there is representation in the history of American comics, and for them to see themselves and to appreciate one of their own.

Michael Swanwick: It was really good to see the Baldo comics done in homage to Gordo.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Hector Cantú, who's the writer for Baldo, and Carlos Castellanos, the cartoonist—they work as a team… Hector was there at the grand opening, and he told this very interesting story. When they first were syndicated early on, during one of their early interviews, someone said, Oh, you're the first Latino comic strip to be syndicated.” And Hector said, “Gus Arriola came before me."

Hector and Carlos reached out to Gus before he passed away and said, “Hey, let us introduce ourselves. We would love to do a homage to Gordo in our strip.” It was a storyline over, I think, five days, with a direct reference to the character of Gordo. In the strip on display in the exhibit, you see their main character, Baldo, and his family. According to Hector, they're not meant to be Mexican or Peruvian or any specific ethnicity. They're supposed to be Hispanic, so that all readers can sort of read themselves in it. Or read any Hispanic ethnicity in it. One of the characters is Tia Carmen, Baldo's great-aunt, and she starts to reminisce of the time she went to Mexico and met Gordo.

Marianne Porter: I love that scenario. She was a young woman then, and she almost had a romance with him.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: What Hector told us at the opening was that they asked Gus to draw a profile of Gordo meeting the old woman in a flashback, in one of the strips and Gus said, "I'm too old. My hand isn't steady. You go ahead, you draw it." They showed everything to Gus before it was published. Hector went on to say that Gus was very gracious, he praised them, and he only made one edit in the strip. At one point the Gordo character was going to say something like "Thank you, senoritas.” The word for young ladies. And Gus Arriola said, "No, that's not what Gordo would say. He would say, palomitas, little doves. Because that's the slang in Mexico" of the time period. This edit makes it charming. So Gus gave him that one edit, and Hector said, “Yeah, of course I kept it.”

They consider him the precursor and they got his blessing. It was very much a professional friendship. Hector and Carlos often talk about the greatness of Gus Arriola, and that without Gordo many in one of the strips newspapers would not be accepting of Latino cartoonists. So they pay him great homage.

Marianne Porter: Well they should, but good for them.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Yes. The other person in the exhibit was Lalo Alcaraz, American cartoonist who is known for his syndicated, politically focused strip La Cucaracha, and who is very well known at this moment. He was a consultant for the movie Coco. He's dabbling in films in Hollywood, and is just a wonderful and talented editorial cartoonist. Since he hit the cartoonist scene, he's always acknowledged that he's walking in the pathway created by Gus Arriola. He did one—because he does sort of single strips at times—where he pays homage to Gordo’s Bug Rogers. And then, when Gus Arriola passed away, he did an essentially In Memoriam strip for him.

These two strips, La Cucaracha and Baldo, for me, would not be here without Gordo in many ways. That's the legacy of Gus Arriola and Gordo. These two strips and many others.

Michael Swanwick: I'd like to comment on the word modernism in the title. It is really striking, when you get to see the artwork close up, how he combined traditional Mexican visual arts with modernism. He could have made a very profitable living as a commercial artist.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: He could have. He was an artist. It's interesting, when we think of the deadlines he had to meet for daily strips, as cartoonists work a couple of months in advance, and all the work involved, it is amazing how quickly and beautifully he drew and told a story.

But nonetheless, two thoughts here. You’re right, he incorporated a lot of Mexican into his strip-- not just culture in the story, but also the visual arts like pottery and craft, which is something that really drew my attention. In the exhibit, I included the strip of the Mexican pottery with the silhouettes around because it was very much striking to me, and because it demonstrated the influence of his early career as an animator on his strip. That's why I had a colleague of mine animate it so that all viewers could see the silhouette figures move—essentially a tug of war between Gordo, Pepito and the animals. I wasn't trying to do a gimmick. I must say, I worried about that. I didn't want it to be gimmicky. I just wanted to show his thinking, artistry, and humor.

Marianne Porter: As you go around the pot, the story unfolds.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Essentially he's doing something like Egyptian vases. He's a narrative storyteller. It was mimicking this old art form. But then, as you see the rest of the strips on the walls, you start to realize he has a pacing that he is also drawing from Egyptian vases. He knows what he's doing consistently. Also, the Mexican pots are a repetitive motif throughout the strip in various ways, whether they're primary focus or whether they're in the background. For example, some of the strips on the wall tell you how to make a pinata using terracotta pots. Mexican pottery appears quite a bit throughout the run of the strip, which is delightful and impactful.

Michael Swanwick: As a science fiction writer, I have a particular fondness for his long narrative stretches. Some of what he wrote was definitely science fiction, including my favorite story in all comics where he meets the his “dream gorl,” his perfect woman, and falls in love with her. Then, slowly, he comes to realize that nobody else can see her. She's a personification of everything that is perfect about women to him. He manages to adjust to this and decide that even if nobody else can see her, he's going to marry her.

Then she doesn't show up one day.

And when she shows, up she explains that there's an Italian filmmaker who has the same dream girl. So they fight a duel for her. Gordo goes up on top of a hill in Mexico and the filmmaker atop a hill in Italy. They fight with their imaginations to visualize her. She fades out and fades back in. And finally Gordo loses and she is gone forever.

It was a heartbreaking little story. I've always loved that one.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: That is beautiful. And you're right. It's something I've given great thought. There are a lot of episodes, that one obviously very special. And I should say there are other genres one could see in Gordo, though, and I know this isn't your question, but I chose modernism as opposed to other topics as a theme to unify a forty-year run strip. Also, I selected modernism to make certain that people could see the artistry of Gordo as well as the storytelling element. As a curator, my job is to create a story that highlights the strip and the cartoonist. And for forty-year run, strip, I choose ‘Mexico’ and ‘Modernism’ because it allows the visitor to walk away from the exhibit, learning a lot, and yearning for more Gordo.

You're right. That episode would have been a beautiful story. But there wasn’t the wall space.

Marianne Porter: I have this crackpot theory about curators, magazine editors, concert programmers--that you're all giving us a map. You're all leading us down a particular path. You have a place you want to bring us to. You just now said that you were trying to make sure that you highlighted this really very long-lasting strip and the artistry behind it. Were there any special points where you wanted us to stop on the path and look at something: smaller but more focused, maybe, or...

Nhora Lucía Serrano: That's an excellent question. There were small special points I highlighted for the visitor. And because I didn't have enough time or enough space to develop them more, I left little clues, hopefully.

Here's the first one that comes to mind. I find so interesting that Gus took the role of Pepito, and had Pepito grew up through the strip. If you remember the exhibit, the Billy Ireland has original artwork in which Pepito is much older, he's dressed better, playing with his uncle, and I make note in a label very quickly that Pepito’s grown up and that this is very much like in the character Skeezix in Frank King's Gasoline Alley. In the museum label, I was trying to connect the dots for the first-time visitor that there's an influence of Gasoline Alley storytelling on Gordo. So that would be one where I was trying to leave little clues for people to ask, “What's Gasoline Alley?” in case people didn't know, and “Really? Pepito grew up? What else is there?” To me it's very important. It's a small one. But one of the important little details for story.

Marianne Porter: Pepito grows up, and Gordo ages a little, but no more than a smidge. And the housekeeper, Tehuana Mama, she doesn't, really. She's got an ageless quality to her.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: She does. Time doesn't really pass for her. Pepito’s the one where we see time passing. Unless we understand the context of the story, the strip doesn’t reflect real time outside the strip. Neither Gus nor the characters make references to the real world. This is something curious, Michael. I'm sort of curious from your recollection of reading the strip. Gus didn't really break the fourth wall and make references to real life historical contexts, would you agree? If anything, for me, he was foreshadowing a lot of art ideas and social topics before they actually happened. There are cartoonists who would bring in political elections or anything else. But Gus really had Gordo in its own universe.

Michael Swanwick: Except for one thing, which is he was an environmentalist who was very concerned about the physical state of the world. To such a degree that, if I recall correctly, the last we see of Pepito, he and his girlfriend or maybe she was his fiancé by then, who showed up first as a little Texan girl, go off in a spaceship to another planet. Because he can't picture a positive future for them here.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: That is true. I have not seen those strips in person. That's through my research. So I'm hoping when I can get to the Bancroft this summer, I can look at those strips and develop that chapter on the environment for my book. But you're right. What we would call today the environmental concerns, he was definitely a vanguard in that sense. That's the only one that he really... I wouldn't say broke the fourth wall, but had a reference to real life outside of the strip. You're right.

Michael Swanwick: But at the same time he was not being overly political. He wasn't pointing fingers at specific politicians or corporations. He was just concerned about the Earth as a whole.

Marianne Porter: There is also coming into the strip an awareness of things that are happening in art and in music, such as rock and roll.

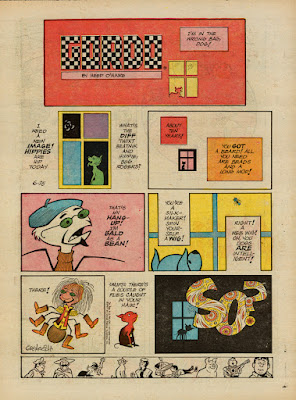

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Yes, there is. One that luckily I put up on the wall, is his fascination with sound, and how to depict sound and music in a strip—he plays with color, layout and font. (There's one on the wall which he signs by Dessie Bell. Decibel. He makes that pun.) But again I would say, he's making reference, perhaps to music or change in music. Right? Bug Rogers is a character referencing the sixties. But he doesn't really step completely out of the strip and make a real-life world reference. I think in some ways he kept Gordo and all the characters within the world of the strip.

I don't know. It's much more subtle in Gordo. It's a different time. Who knows? If he were writing today, would the sense of time and sound be different?

In answer to a question you haven't asked, which is why, when you first walk into the exhibit, the first thing you see from a distance is a large decal of the comic strip blown up on the far wall, what I call the intro and welcome wall to the exhibit. I wanted all of you to walk into the strip metaphorically and literally. I wanted people to feel what I call the Mary Poppins moment, where you could step into the comic strip and into Gordo’s world. Also, when you first walk in, the immediate thing that your eye catches is the A-frame display case, and what I wanted the viewer's eye to go to was a photo of a young Gus Arriola with an accompanying label saying: Cartoonist, Illustrator, Artist—he has many identities. And then below this photo, you have the end of Gordo, that big of blow up of Tehuana Mama and Gordo dancing together.

To me it's a strip of love, the whole thing. Whether people were falling in love or not, there was love infused in all of this. He loved his characters, he loved this world.

Marianne Porter: And the characters all love each other. They all care so much about each other.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: They do. The animals are so fun. They're family.

Marianne Porter: I like the drunken worms.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Oh, my God! The drunken worms are just hilarious. In making decisions of to what put up on the wall, I was trying to include as many of the animals so the exhibit would have a little bit of everything, thus, the worms had to go up. Because they're funny.

And they're inebriated.

Michael Swanwick: Pixelated.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: There we go! Well, and in that last wall, I wanted it to be about all Bug Rogers, because I think there was something very special with that character. It was one that really offered, like all the animals, but more so insight into life. Bug Rogers really offered the philosophy of life through commentaries, and it was very profound, even though, when you first see and read it you think, “Oh, that's fun and funny!” And then if you read it again. You're like, "Oh, that's pretty profound."

And the animals all offered that type of insight. Also, I was hoping that the show would attract families on weekends. I wanted children to be exposed to the strip. As children, we read things and catch something, and I thought the animals will catch their attention and see the playfulness of the strip. I think the animals are fun.

Marianne Porter: Oh, absolutely. I thought both the text and the signage, the graphic imagery, were really good and really involving. The fact that you, when you get off the elevator, there's a group of the character running along the wall, and you just run along with them and then get you to where you need to go.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Thank you, I would say that's something the Billy Ireland has been trying to do with the decals for all of their exhibits to help the visitor know where it is located.

Going into the Billy Ireland, you have to go upstairs, whether by stairs or elevator, and you have to go around the atrium. And so finding a decal that is essentially running also helps lead the visitor to the gallery. Also, the decals on the gallery wall were very strategic. I wanted them to reference the very walls on which they are located and allow people to see a snippet of the strip but bigger. One of my personal favorite decals is in the corner when you go from the Mexico section to the bean sections. In the bottom corner there is a yuca plant in two colors—the left part of the yuca is light green whereas the right part of the plant is teal in color. This yuca plant extends from one wall to another, which is mimicking how it is in one of the Gordo strips, where it extends from one panel to another.

The other decals are also quite charming and eye-catching: Gordo carrying the bean pot while running along with Pepito and the animals, the kids reading the newspaper, and Pepito as a modernist artist wearing a beret while drawing.

The other great decal in the exhibit is the one where there are a lot of the sleeping animals—it is located on an inside wall as you go into the other gallery; they're taking a little nap as you leave the show. Just little moments like that I hope are fun for the museum visitor and the Gus Arriola fan. Mostly, these choices are a reflection of the fact that I wanted the strip to speak for itself. Yet there are choices you have as a curator, one which I was asked by the Billy Ireland staff was, "Do you want the wall painted a certain color?"

Keep in mind that the Billy Ireland staff is very generous and supportive. They seek to support the curator’s vision as well as the comics. Back to the wall color question --I said, no, I want the strip to jump out so let’s leave the walls white. And so, it occurred to me, I want the decals from the strip, and I want them to jump. And voilà we have decals everyone giving the visitor small windows into the strip.

Michael Swanwick: I understand you're working on a book about Gordo. Can you tell us about it?

Nhora Lucía Serrano: Yes. Obviously an exhibit like this is a great beginning for the book. But as we've talked about, the exhibit can't cover everything that a book can like, as you mentioned, episodes and stories… There are certain choices I had to make and couldn't cover everything. And so I'm working on a scholarly book with hopefully a lot of images. I'm currently speaking with a couple of publishers to see who would be interested. There's many books about cartoonists right? There's books on Charles Schultz. There's books on George Herriman. I want to write a book that essentially talks about what Gus Arriola did. And to think of it, I see a chapter or early chapters on his relationship to not just animation, but George Herriman’s Krazy Kat and Li’l Abner. Where did this come from? What the exhibit gives you, going back to your earlier question, is only a little tidbit of what the influences are. I just did those two display cases, and it was very quick. To me, that's a chapter discussing where does Gordo fit in? What were the influences? Where was he borrowing? What was he changing? What was he innovating?

And so, to your question. I am writing a book because, to be honest, no one has in written such a book, and I think it's needed. Obviously, to talk about the strip and hopefully go more in depth into the storylines. Right? I see a chapter about storylines which the exhibit doesn't have. And also I want to have a chapter that discusses more in depth modernism. Returning back to the labels, I really appreciate your kind words about the bilingual signage and all the decal images. But a label's only this big. It's not a chapter.

So there's stuff I want to write more about that's already on the walls. Part of this reasoning is because I didn't want the exhibit to be very text heavy. I was conscious of that there was enough words on the wall because of the inclusion of Spanish and English, which was a balancing act of space. I was mindful and concerned to not write too much text for the labels because I wanted the actual words of the strip to jump out.

Marianne Porter: To speak for itself. Yes.

Michael Swanwick: I will definitely buy that book.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: That's what I'm working on. And I'm trying to find a publisher that will allow me to put in a lot of color images, because I think the color is important to the Sunday strips. Because he plays with color. Not in all of them. But they're beautiful.

Plus a lot of people have reached out to me, asking, Is there going to be a catalog for the exhibit? No, there isn't. It isn't something the Billy Ireland does. But they/we are coming out with a booklet for the exhibit, and their communications office should be finishing it soon so it can be available to all visitors. The booklet has some of the colorful strips in it.

I've been writing a lot of stuff in the past year about Gus, so I'm on my way to finish my book soon. But I also want people to feel… that this exhibit was not not just a two-year project. This has been a labor of love, and the thought that it's going to come down in May, it's a little like my child is going away. So I feel very much responsible to make certain that the exhibit continues in other forms. My lifelong goal of making sure that Gus Arriola is part of the conversation about American comics continues beyond this exhibit. And so that's another reason to write the book, to keep Gus Arriola in the conversation about a comics canon and to establish him firmly in the history of American comics.

Michael Swanwick: Okay, have we left anything out, Marianne?

Marianne Porter: I think we did it.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: I'm trying to think, too, if there anything else. Oh! I put a bench in the exhibit, so families could sit down, something the Billy Ireland hadn't done before, but I think hopefully lets it be a family show.

Michael Swanwick: As somebody who likes to linger over a show, I appreciated that.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: One other thing. In the display cases is a artifact that I loved and I still love. We included a Gordo strip in the display case and not on the wall, and the reason why it is not on the wall is because the strip is about when Gus Arriola is sick, and so Gordo talks to Pepito and goes. “Oh, the artist is sick.” And you see him in this bedroom. Essentially, Gus Arriola is sleeping, and someone else is drawing the strip. The person who drew that strip was Eldon Dedini. What happens if you're sick and you can’t make your cartoonist deadline? You call your friends! And so that's something important to highlight about the history and process of American newspaper comics—not just for Gus Arriola or Gordo, but for anybody involved in cartoons back in the day. You called your fellow cartoonists who helped you out. I think it's a really interesting meta-reference in that strip where you, you know essentially, Eldon Dedini is the artist. You know the cartoonist is sick. Somebody else is stepping in, and you see the communication in the draft drawings on parchment paper that went back and forth between the two men. Where Dedini was sending it to Gus to see if it was okay.

Michael Swanwick: Hmm, that's good.

Marianne Porter: Yeah, yeah, that's again connections with all of the rest of American comics, and how it all intertwines.

Michael Swanwick: I found it very odd at the end that Tehuana Mama, who through the entire strip has been the hired housekeeper...There was never any hint of romance between them, and then, at the very end, to finish off the entire strip, Arriola married them to each other Tehuana Mama and Gordo. That was such a strange thing for him to do.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: It was a strange thing, I would agree with you. In interviews where he talked about the end of the strip, he said he didn't want his character to be lonely. He wanted Gordo to go off into the sunset, and be happy. So he married them off. His son, Carlin, had passed away--what was it?—ten years before the end of the strip. Gus was getting older. The laborious task of doing daily strips, Sunday strips, all of that... He was just tired. He said it was time.

He was sad. He was grieving still, and so I don't think he wanted to end on a somber note. He, I think, in many ways since this was his body of work, he wanted to have his character ride off into the sunset. Which, literally, is the last strip. They go on the bus, and they ride off into the sunset.

Michael Swanwick: That sounds good. Yeah.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: A very Hollywood kind of ending. If you think about it.

Michael Swanwick: The image of the two of them dancing is very sweet.

Nhora Lucía Serrano: It is very sweet. We also can't forget all of us when we think of it, that he was with his wife, Mary Frances, his whole life, and so he had a very supportive partner whom he met at Screen Gems right, Someone who helped him out with the strip. And so, in many ways, I think the ending is also an homage to his love and dedication to Mary Frances and Mary Frances to him.

Above: Images courtesy of and used with the kind permission of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum,

*

There's another pun in the ant's line, btw, at the end of the last image: "the living dad". I also noticed a certain level of referencing the real world in the acknowledgment of beatnick vis à vis hippie, in the penultimate image with Bug Rogers. Or perhaps those two archetypes were just simply too universal not to be part of the Gordo world as well.

ReplyDeleteThat exhibit looks fascinating. I have only the vaguest memory of Gordo, really only that I must have read the strip at some point because the characters looked so familiar. Back then, I was not a critical reader (for that matter, I'm not really now), and certainly did not think of comics or cartoons as being an art form. Looking at those panels now, I become keenly aware of how much I missed by being too young -- the art is extraordinary.

Thanks for posting this interview, Michael.

Forgive me, I hit "post" too soon, before also thanking Nhora Lucía Serrano for this exhibition, even though I am only able to view it vicariously, and Marianne Porter for her excellent questions.

ReplyDelete